The Peak

Conversations: "Slowest Hunter" by Swati Sudarsan

Blog Editor Chase Isbell interviews Shenandoah contributor Swati Sudarsan about “Slowest Hunter,” a dystopian short story about celebrity culture.

Books: Night Watch by Mathew Goldberg

Blog Editor Chase Isbell interviews Shenandoah contributor Mathew Goldberg about his book Night Watch, a short story collection about the violence of ordinary life.

Small Town Dispatches: Tabish Khair

Special Features Editor Nadeen Kharputly chats with Shenandoah contributor Tabish Khair about living in Hornslet, a small town in Denmark.

Conversations: "This Is My Face When You Won't Stop Talking" by Flávia Monteiro

Blog Editor Chase Isbell interviews Shenandoah contributor Flávia Monteiro about her creative nonfiction essay “This Is My Face When You Won’t Stop Talking” featured in Issue 74.1-2.

Books: What We've Become by darlene anita scott

Blog Editor Chase Isbell interviews Shenandoah contributor darlene anita scott about her poetry chapbook What We’ve Become, a collection about love.

Behind the Poem: 82Pb :: Head like a Hole{I’d rather die—}

Rosebud Ben-Oni introduces her readers to Plumbum, the element that animates her Atomic Sonnet with its propensity for destruction and an affinity for Nine Inch Nails.

An Interview with Jean-Luc Bouchard, Shenandoah's New Creative Nonfiction Editor

Blog Editor Chase Isbell interviews Jean-Luc Bouchard about his new position as Creative Nonfiction Editor for Shenandoah.

Small Town Dispatches: Mathew Goldberg

Special Features Editor Nadeen Kharputly chats with Shenandoah contributor Mathew Goldberg about living in Rolla, a small town in Missouri.

An Interview With Lesley Wheeler on Mycocosmic

Shenandoah intern Ellis Nicholson sat down with poetry editor Lesley Wheeler to talk about her sixth poetry collection, Mycocosmic, and her writing process.

Shenandoah Interviews State Senator Ghazala Hashmi

In 2019, Ghazala Hashmi, a former English professor, became the first ever Muslim and Indian American State Senator in Virginia. In another historic feat, she won the Democratic nomination for Lieutenant Governor in June 2025 and will appear on the ballot for the statewide election this coming November. Shenandoah’s Special Features Editor, Nadeen Kharputly, sat down with Senator Hashmi for a conversation about her early life, her career in education, her transition to a political career, and how literature has shaped her life—and her desire to make life better for her constituents.

Curating Connection Through the Art of Vulnerability: A Conversation with Stevie Billow

Shenandoah intern Kaia Beddows sits down with nonfiction editorial fellow Stevie Billow for a conversation about their writing journey, creative inspirations, and the curation behind the essays featured in Shenandoah’s 75th anniversary edition.

Small Town Dispatches: Holly M. Wendt

Special Features Editor Nadeen Kharputly chats with Shenandoah contributor Holly M. Wendt about their experience living in Annville, a small town in Pennsylvania.

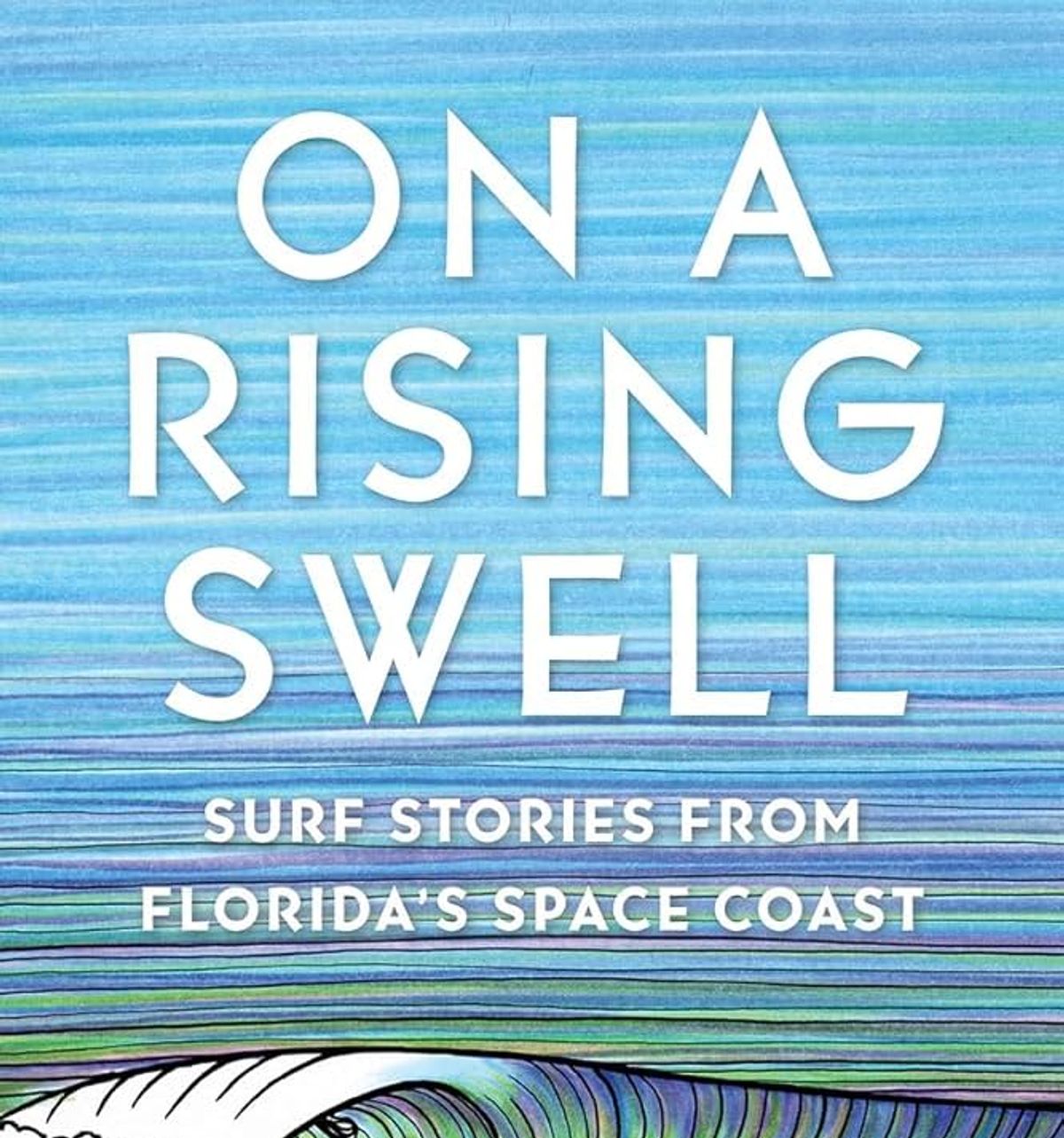

The Periods Between the Waves: An Interview with Dan Reiter about On a Rising Swell

Contributor Dan Reiter discusses his new book On a Rising Swell: Surf Stories from Florida's Space Coast. You can find his short story "Deep-Water Drift" in Shenandoah Vol. 65.1 Fall 2016.

Small Town Dispatches: Robin Gow

Special Features Editor Nadeen Kharputly chats with Shenandoah contributor Robin Gow about what it’s like to live in the small town of Breinigsville, Pennsylvania.

The Interview Proper: Qiana Whitted, Guest Comics Editor

In this interview, guest Comics Editor Qiana Whitted, discusses her lifelong love of comics and her experience editing the comics section of Shenandoah's 75th anniversary edition.

Attraction in Truth: An Interview with Martin Cloutier

Shenandoah contributor Martin Cloutier discusses the interplay between gender and romantic attraction as explored in his debut novel, as well as his unflinching commitment to truth telling in his work, and the ways he achieves it. Cloutier’s flash fiction story “Punishment, Inc.” was featured in issue 63.1. Find it here.

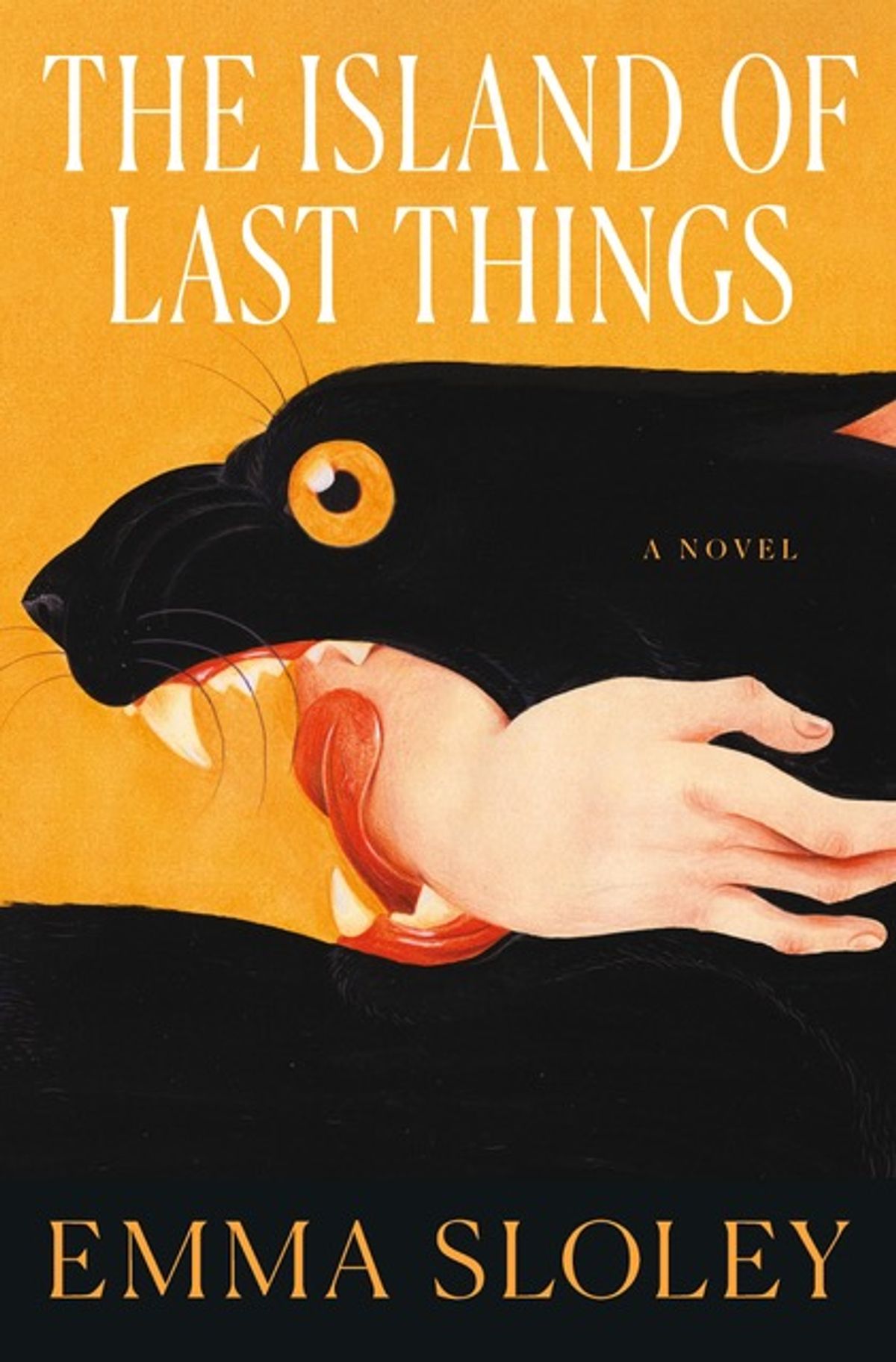

New Novel Q&A: The Island of Last Things

Contributor Emma Sloley talks to us about the release of her new novel, The Island of Last Things. Emma’s story “Sugartown” appears in our 75th anniversary issue.

Small Town Dispatches: Matthew Vollmer

Special Features Editor Nadeen Kharputly chats with Shenandoah contributor Matthew Vollmer about what it’s like to live in his small town of Blacksburg, Virginia.

Small Town Dispatches: Sonya Lara

Special Features Editor Nadeen Kharputly interviews Shenandoah contributor Sonya Lara to gain insights about what it’s like to live and write in the small town of Ripon, WI.

Cover Reveal for The Shipikisha Club

We’re thrilled to help celebrate the forthcoming launch of Mubanga Kalimamukwento’s novel The Shipikisha Club, out from Dzanc Books in March 2026, by collaborating on the reveal of the cover, designed by Michelle D’Urbano.

Excavating and Deconstructing: An Interview with Shah Tazrian Ashrafi

The short story “Camp” by Shah Tazrian Ashrafi, appears in volume 74.1-2, our 75th anniversary issue, and explores the dystopian world of a mother who has lost her daughter in an accident. “Camp” is a place where parents who have lost their children can go and find a child to replace the one who has died. The story explores many facets of grief, and we talked to Shah about where the idea for the story came from, the power of a good dystopia, and his literary mentors.

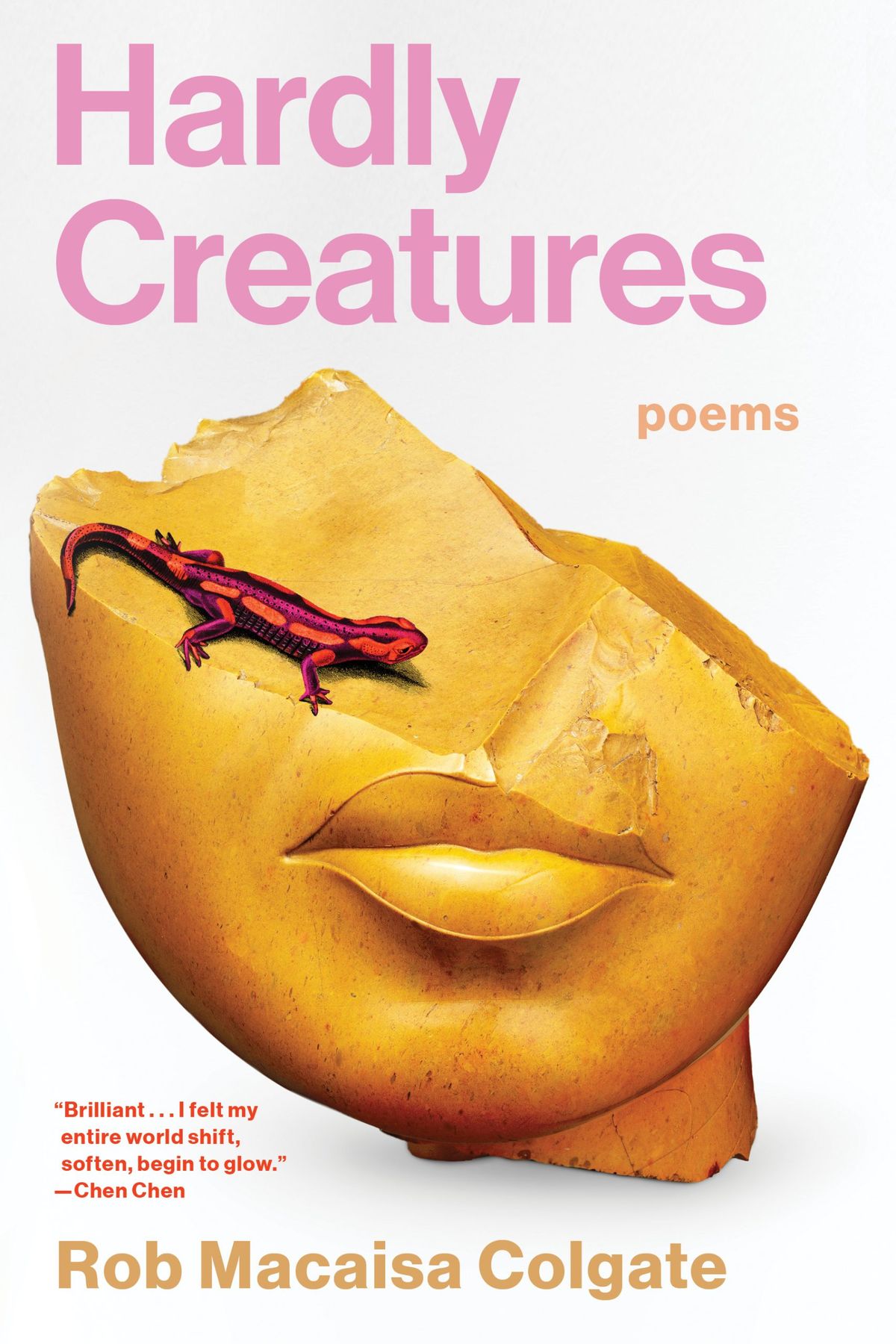

Writing as an Organ of Accessibility: An Interview with Rob Macaisa Colgate

Contributor Rob Macaisa Colgate highlights the significance of collection, reflection, and accessibility to the process of creating their debut. Rob’s poem “The Body Is Not An Apology Except For Mine Sometimes” appears in issue 74.1-2.

Beyond the Watershed: Q&A with Nadia Alexis

In this Q&A, Nadia Alexis talks about her new collection of poetry and photography, Beyond the Watershed, which focuses on various experiences of a Haitian American daughter and her Haitian immigrant mother.

Black Women Writing: A conversation with two Shenandoah Editors

Nonfiction editor DW McKinney and former associate editor Moriah Katz have essays in the anthology Mamas, Martyrs, and Jezebels: Myths, Legends, and Other Lies You’ve Been Told About Black Women (Black Lawrence Press, 2024). Corresponding through a living document, they discussed their individual essays, their dream anthologies, and taking up space as Black women writers.

Small Town Dispatches: Megan Mayhew Bergman

Special Features Editor Nadeen Kharputly interviews Shenandoah contributor Megan Mayhew Bergman to learn about what it’s like to live in her small town of Shaftsbury, VT.

Small Town Dispatches: Ann Fisher-Wirth

Special Features Editor Nadeen Kharputly chats with Shenandoah contributor Ann Fisher-Wirth about what it’s like to live in the small town of Oxford, Mississippi.

Grief in the Earth: A Conversation with Desiree Santana

Shenandoah contributor Desiree Santana discusses what shaped her poem “The Starving Time,” which was a runner-up for the Graybeal-Gowen Prize and appears in issue 73.2.

Deleted Scenes: Insight into Revision with Michelle Donahue

Shenandoah contributor Michelle Donahue shares some of her revision process for her short story “Moon Jump,” which appeared in issue 73.2.