Insomnia and Sleep Notes

by Jenniey Tallmani.

Tonight, you will rise at the sound of the cat howling in the kitchen. Tonight, you will rise and go where you are beckoned, down the stairs to feed the insulted one—whose dinner has been forgotten, whose neck craves your fingernails. Tonight, you will rise to check windows and doors, to find lights lit and click them off, to adjust the couch and replug the phone and stare into the fish tank.

Tonight, you will rise to sit on the kitchen carpet and scratch your cat, who knows nothing of restless or daylight saving or the confusion of rising at 2 a.m. to return to bed an hour later finding it still 2 a.m.—and isn’t this empty bowl, this light and locked door, this fuzzy puddle who loves the night (about whom you think if she could name paper would call it poem), isn’t this a metaphor for anything?

ii.

I did not have insomnia until I had children. Three sons, one born every twenty-one months—something about seven years of sleep deprivation and constantly being on alert for any manner of noise or threat. My mind can’t sleep anymore.

iii.

O, insomnia, before you I kneel

in awe: you brute, you rascal, you midnight prince.

In + Somnus + Sleep

O, insomnia, if you were ever to leave me I fear

I would sleep myself to death.

iv.

The youngest child, Cedar, was born a month too soon and, as an infant, laughed at the ceiling for a full month—the month of his earliness, not yet human. Some nights he sleepwalks—talking, moving, dancing, walking into his brothers’ rooms, climbing onto their beds, rearranging their pillows, and taking their coveted things. But it is very terrible when the terrors come—I cannot wake him, cannot bring him back to this world, and he is so alone, so scared inside his head looking as if he has just watched his family abandon him—I call everyone into the room. We wait for him to come back, we wait, cooing soothing words at him, whispering our love so when his worlds are finally united again, his eyes focus and he laughs at us, what are you all doing in my room? But we are hugging him, kissing him, telling him we love him, and saying, Poor Cedar, Sweet Cedar.

v.

Sleep disorders run in families. Parents with insomnia are more likely to have children with insomnia. Sleepwalkers are likely to bear sleepwalkers. Traumatic childhood experiences increase the risk of sleep disorders. This can be passed down generationally. If you are a night person, your children are likely to be night people. Nature / nurture is only barely at play here.

Biologically speaking, sleep is a mystery. In sleep, we, as animals, are at our most vulnerable—yet we keep doing it, spending a third of our lives knocked out, exposed, asleep. Research continues to ask questions regarding why we sleep at all. We know why we need it; we know what happens without it; but we still do not really understand why we do it. Ever since it was recognized to be genetically linked, scientists have been working to develop ways of understanding the mechanisms of sleep and identifying the genetic link to sleep disorders.

My oldest son claims not to dream, as does my husband. I cannot understand a life without dreams. I consider my dreamlife to be nearly as important as my waking life. I’ve learned nobody wants to hear about my dreams, though—best to keep them to myself. This is difficult because I hold grudges—when my husband betrays me in a dream, I have a hard time letting it go the next day. The youngest turns to Wikipedia, his go-to source for answers, and returns terrified of the stories of sleep-walking killers he finds on the “homicidal sleepwalking” page. So, we find new stories. New myths. This draws us to the Egyptians.

vi.

Sleep paralysis is the experience of waking up from sleep, but only your mind wakes. The body is paralyzed. This can last for seconds or minutes but feels like hours. I passed this affliction on to both my youngest sons, along with lucid dreaming. We are a people that don’t have clear lines between asleep and awake.

When I was four years old and sharing a room, my older sister and I took turns tickling each other’s back to go to sleep, drawing the alphabet in big swoops until the other guessed the right letter. There was a big mirror hanging on the wall of that room, and on the darkest nights, an old woman with an ugly face sat on my chest. One night, that old woman was sitting on me, staring into my eyes, and I was yelling as hard as I could, but no sound was coming out. No matter how much I willed my body to move, I couldn’t even roll over or blink.

I now know this disorder has a name and its very own entry on Wikipedia with paintings of the “night hag” that go back centuries (a familiar vision), but I was young and my eyes told me a witch was pressing the life out of me. When I managed to free myself, I knocked into the wall, shattering the mirror. My mother came into the room before I could hide the mess, and she started picking up shards of mirror and yelling about all the bad things that would happen because of my horsing around—always superstitious, she threatened bad luck. She had also warned me to never die in a dream, a fear that followed me well into my twenties. The Egyptians, however, believed it was good to see yourself dead in a dream—it meant long life.

When he was eleven years old, Cedar, the somnambulist, tried to walk out of the tent he was sharing with his brothers in the Theodore Roosevelt National Park in the middle of the night. His escape was foiled, however, because he was dreaming he was a cat and, being a cat, could not work the zippers. His brothers woke up to him meowing and scratching the fabric. This was not his first time becoming a cat. Once when he was sick, he got stuck in a sleep-trance and became one for fifteen long minutes—clumsily petting my face and hair until I nearly started to cry from the sweetness of his soft clawless knuckles, his fingers curled under like paws, how his hands grabbed onto my face with such sturdy devotion.

During these incidents, I must talk him back to sleep. It is a very careful dance. You do not want to wake a sleepwalker, believe me. You may turn a gentle dream into a night terror. So, I ask him questions to be sure he is sleepwalking—it is harder to ascertain than you might think. Where are you? (In the living room.) Who am I? (Mama.) Sometimes he answers every single question correctly until you strike on that one fact you barely thought to mention, but proves he is asleep: What is your name? (Bucky.) The cat from the comic book he was reading before bed—not Cedar. Cedar is asleep.

And then, as if the jig is up, he knows too and stares right through me. He dives for an invisible bug on the floor. Eats it. Giggles. Stands up and walks into the other room. Lifts a cup from the table and sets it back down into thin air where it smashes to the floor. So, I guide him to his bed or to the couch. I tell him he is dreaming and it is time to go back to sleep. Brush my fingers through his hair and sit with him until he is out. And then I stay awake all night guarding the door, sure he will sleepwalk away from me and be lost to the cities at dawn.

vii.

The ancient Egyptians believed that in sleep some of us were more talented than others. They are said to have developed an advanced practice of conscious dream travel. Trained dreamers (trained dreamers?) worked as seers and practiced shapeshifting—crossing time and space in the bodies of birds and animals. Through this travel, they explored the afterlife. They explored worlds. It was believed that true initiation and transformation took place in a deeper reality reachable through the “dream journey.” A rightful king was one that had the ability to travel between worlds. I am an atheist. I don’t know why I find all of this so fascinating, but I begin to call us Prince Cedar, son of Jenniey, travelers of dreams.

In the 1990s, Thomas Wehr’s rather well-known sleep study found that people sleep most naturally in two four-hour phases with about an hour of wakefulness between. Roger Ekirch reports the same in his book, At Days Close: Night in Times Past. “Waking up directly after dreaming allows people a pathway to their subconscious.” Getting out of bed right away, as soon as the alarm rings or the sun blasts through the window, has denied people “a critically important part of their lives—their dream life.”

The similarity between Ekirch and the ancient Egyptians’ language is comforting. But I also know the difference between insomnia and wakefulness. Insomnia is the room you are in a full three hours after waking in the middle of the night, where you are beginning to hallucinate, hyperventilate, and panic. Insomnia is a terror that breeds itself. Insomnia is an abyss.

viii.

After so many years of it now U learn a new way 2 rest where rapid eye movement does not insist distress b/c once U were awake on a 3 day stint of sleep refusal & finally broke down at 4 a.m. — a tree quaking in wind / a splash of meteorite from Jupiter — (U see it coming PREDICTABLE / UNSTOPPABLE & if U-R not in bed hallucinating / fighting the urge 2 scratch the walls / scream in the bathroom / U-R on the kitchen floor petting the cat again) so from then on U no longer aim 4 sleep but lie calmly in bed not expecting it any more than a meteor / an earthquake: close ur eyes & listen thru earbuds 2 MTM / Cristina & Meredith / Olivia & Abby / Clair / Niles / Sam & Diane where Everybody Knows Your Name & it lulls U / even if it does not lead 2 rapid eye movement — it lulls U.

ix. (for the cat)

1

the cat sees words

ants marching the page

2

her favorite spot any spot

where paper crumples

and when I nest

among the pages

(as I like to do)

she stretches long

to touch them all

3

scratches outRAIN lies

down onFROGS sniffs

DIRECTION cautiously

drifts to sleep

head pressing ELEVEN YEARS AGO

and claws grabbing

WINDOW, TRUCE, & FACES

4

the cat breathes

as poets do

slow, deliberate, suspicious

5

the wetness of her pink nose

has chosenCENTURY

6

and where she sleeps a sacred place

a good poem where she sleeps

7

the cat’s poem:

ROUSING BOUNDARIES

BETWEEN

CENTURY

were she capable (I feel certain)

she would not conjure centuries

8

Today is a good day indeed

I have scattered POEM

All over the bed

9

We once made her a bed, but she refused it

until a crumpled piece of paper was stitched

to the top. Disdainful of blank pages

preferring (as I do) the touch of ink

shadow of staple-lift / crinkle of edge.

Where my pen goes, her nose follows.

I believe (truly I do) that if I envy her

soft clumsiness as she scrambles from bed

to shelf, she envies me this slide of pen. This

throw of words.

x.

Tonight, I was raped in a dream. I was just here, alive, in my neighborhood. Taking out the garbage. And then I wasn’t. It was a dream; it did not happen; it was not real. He did not grab my wrist. I did not feel the weight of him and in that instant, know, just know, my life was over. Of course, I fought.

Yesterday, I was telling Cedar how awful it is when a cat dies. I’ve seen it. I’ve been there. I’ve held one while it purred, even in death, purred, even with its guts on the ground beside it, purred. I told him so he’d stop saying ignorant things about how cute cats must be even when they’re dead. Told him how a cat doesn’t want to die. Even when it is clearly dying. How life resists death. How life resists even the possibility, the inevitability, of death.

So, I fought. Even though, from the moment that man’s hand grabbed my wrist, I knew my fate. When I was a child, nine years old, I was raped. I don’t know if I yelled or resisted. I was very young and small. They were a group of boys—older and stronger than me. I convinced myself I made the whole thing up for a very long time. I did not tell anyone about it. I got mononucleosis, stopped eating, stayed home from school for a couple of weeks, and piled all my stuffed animals in the bathtub and slept with them until I forgot.

This nightmare was bad. After they raped and killed me, I did not know I was dead. I could still see out of my eyes. But, very much like sleep paralysis, I could not move my body and I could not make a sound. And then a different man appeared over me, and his face was kind but sad. He leaned over my body and brushed my eyelids closed, and then I couldn’t see either—only think and hear. And I knew my family would come and see me like that and think I was dead. And, I was dead. But I needed them to know that I wasn’t dead like that. I was still there. I could hear them. I loved them. I was so worried my sons would think I died like that. I wasn’t thinking of being raped or being afraid. I was thinking of them. I was thinking of other things entirely.

It was a trick I learned when I was nine: how to leave a body.

xi.

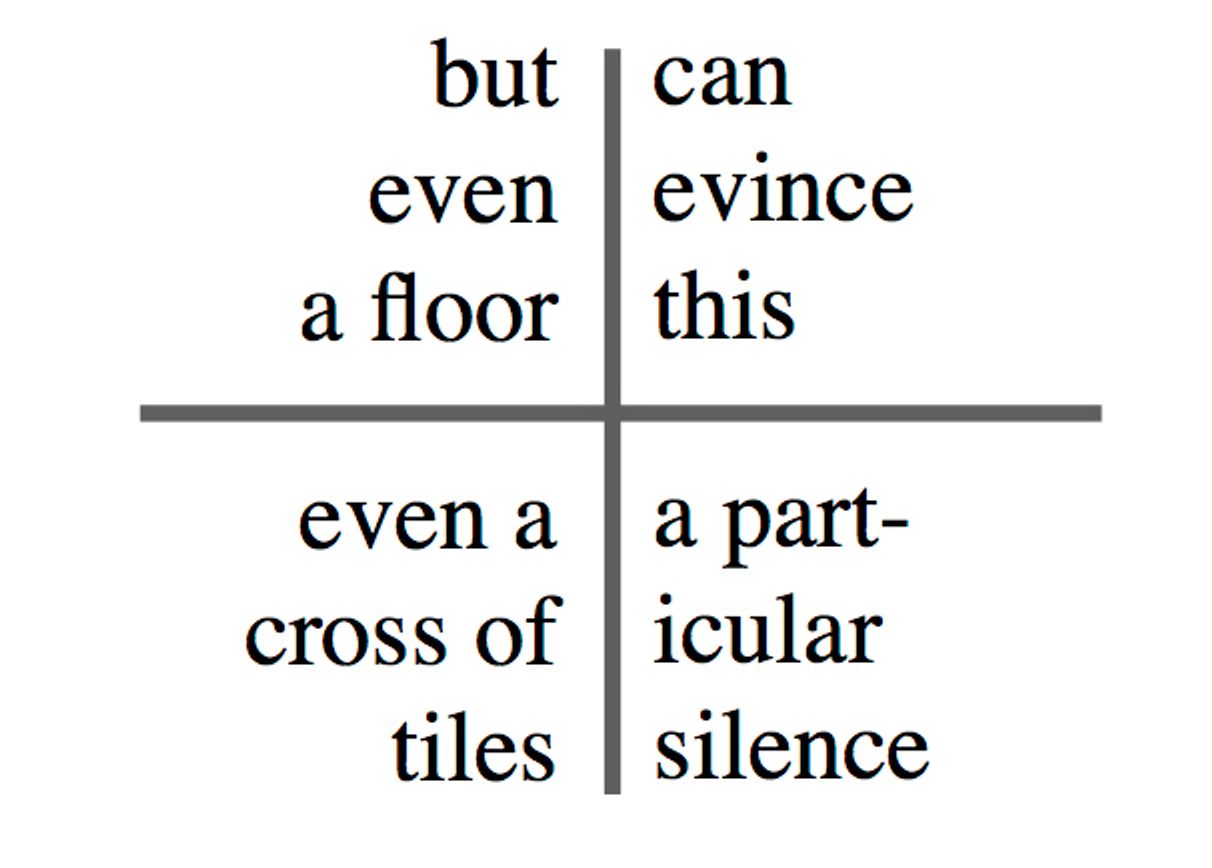

There are 4 tiles on the bathroom floor and if you ask where I’ve been—I’ve been to where they meet.

Excavate the bathroom corner. Explore rage. Ask those ghosts what makes them cry. Where do they find joy? Why do they keep showing up in the bathroom, screaming?

Like in the dream where you cannot swallow. Your mouth begging water and getting none. How you scream mute, thinking you will drown on air—what would you call that?

Tonight, I read a study that suggests your mind still works after you are dead. A burst of brain energy—brief, they say. But consider this: when I have passed out for no more than a few seconds, I think I have been asleep for days; when I am stuck in sleep paralysis, I lose all sense of time; and at two o’clock in the morning, insomnia lasts longer than at any other hour. What if that brief burst of brain energy is the same? Infinite time. I decide to write limericks instead of reading anymore death studies.

(limerick interlude)

Insomnia loves to come creeping

Leaving you powerless and weeping.

You visit the fish

and ask for a wish

but it turns out the damn fish are sleeping.

||

There was a young lady red-headed

who was every night laid and abedded.

Despite what you’re thinking—

I feel your cheeks pinking—

‘Twas insomnia and you’ve been misleded.

||

Night after night, me I tuck in

to a bed that I rarely have luck in

though nightly I try

as the moon lights the sky

at four, dreams of sleep me I chuck in.

||

Insomnia’s a sleep state complex

Whose intent wanders rarely to sex;

It’ll come for the virgins

And a young man’s perversions

But will leave you poetically inept.

xii.

Like any Nymph amongst the reeds they’ll take the freckles, those Potamides, of young girls bathing in their streams; and watch out they will drown young men, or else bestow upon them, that awful gift of Poetry—turning freckles into poems. Or so you think.

Like all Naiads, the Potamides were River Gods’ daughters, favoring young girls (don’t they all?).

In the Lonely Hour, offer them Milk & Honey. Oil, but never Wine.

“What does this have to do with insomnia?” you ask.

“Late Night Mythology,” I reply.

xiii.

All the fish are dead. OLIVIA went first, named for the storybook pig—a smudge of pink across her lips. DIGGER died next, though barely. I kept him alive for an entire week in a blue bucket in the fridge. TURTLE, the beautiful one, survived for ages, but finally nose-dived to the corner of the tank and mostly stopped breathing. I calmed her with clove oil until she slept and then finished her off with rum and sherry. An honorable death.

ALBERT was my favorite—a ghostly white koi who hid for two months in the blue teapot, before finally making friends with the goldfish; alas, he enjoyed this freedom too much, so landed on the floor in the middle of the night where he probably flopped dying for hours—but I did not come downstairs that night, though the darkness called, as usual.

“It is just a fish,” you say.

“But it was ALBERT,” I reply.

And I wasn’t even asleep, busy pretending instead to not have insomnia.

In the Book of the Dead, two mythological fish are mentioned. The ÅBṬU and the ÅNT. These fish were supposed to swim on each side of the bows of the boat of the sun god to drive evil beings/things in the water away from it. I imagine this as fish protecting a very important cat, rowing a boat through the Nile. Life is a storybook at 2 a.m.

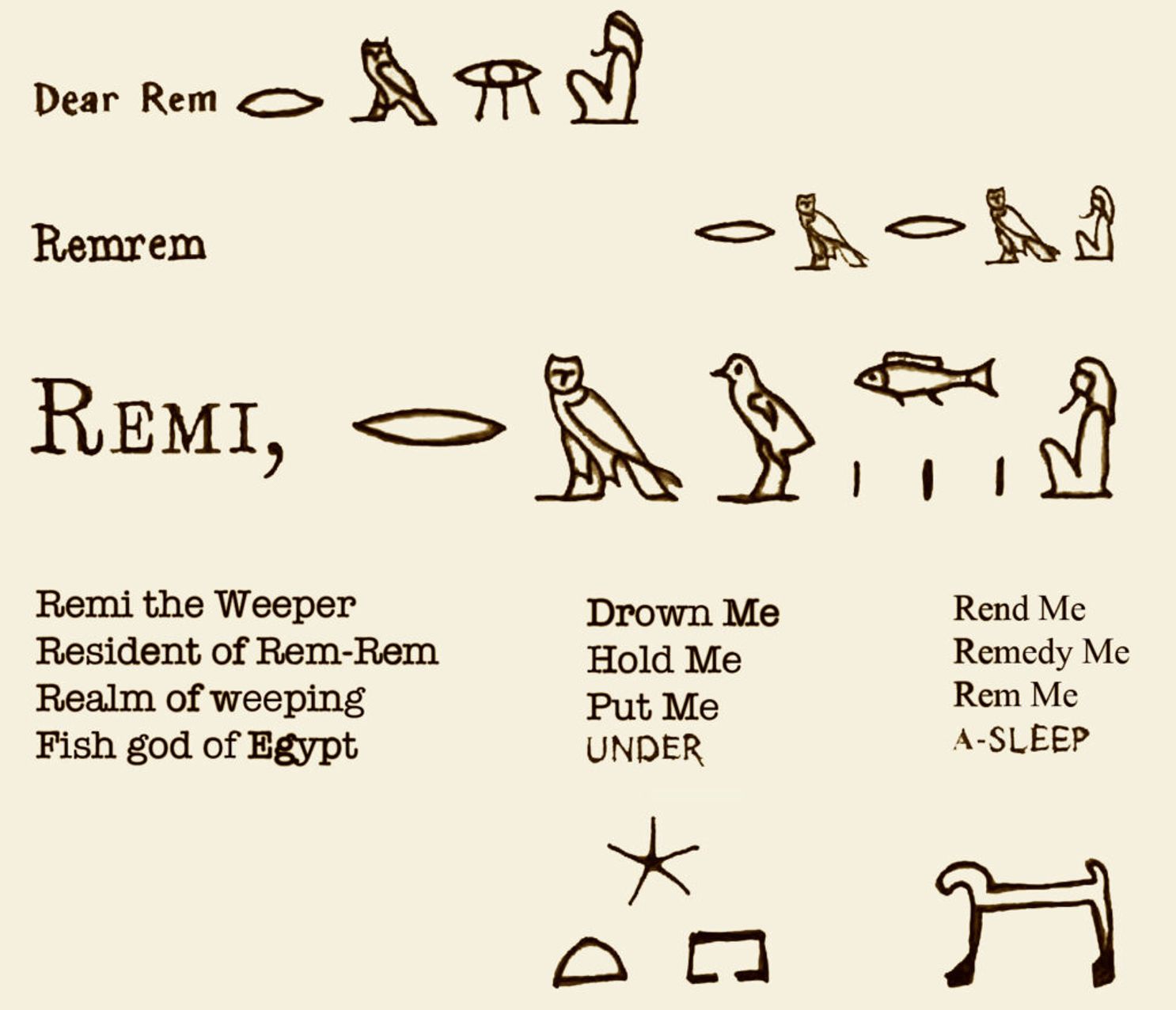

xiv.

REM was an Egyptian fish god. His name means to weep, and his tears were thought to be fertilizing: corn was sown and reaped amidst his weeping. He is one in the same as REMI, the crocodile god who is connected to a vague primitive deity symbolizing the primordial deep. Crocodiles were abjectly feared in Egypt, which means they too were worshiped devoutly.

Monuments and inscriptions contain evidence that the greatest reverence was paid to the cat throughout Egypt. Their cats were fed bread and milk and slices of fish pulled from the Nile. They called them to meals by using special sounds. Cat bodies were treated with the same respect as human bodies. To kill a cat, on purpose or not, was punished by death.

The cat was sacred to Bast, the goddess of Bubastis, and was thought to be her incarnation. Its cult is very ancient; as a personification of the sun god, the animal played an important part in Egyptian mythology. MÅU (cat: pronounce it mow, like wow; sounds like meow, doesn’t it?) is the personification of RĀ himself.

The Egyptian texts prove beyond all doubt that the Egyptians worshipped individual animals, birds, and reptiles from the earliest to the latest times. Before about 3000 BC, this was one of the most popular religions of the Nile Valley. Gods gave and took resources necessary for life, so they, in their animal forms, were all worthy of worship. The ancients would have had little control or understanding of their world—a world where people prospered or suffered based on whether the rains came, how deep the floods roared, and how bountiful the crops.

xv.

The world is magnified at this hour. All your masks come off. You are sitting alone in a dorm room—Sartain Hall: Philadelphia, P-A; year 2000—trying to negotiate a path (without being seen by the girls piled on Becca’s bed watching VHS tapes of Dawson’s Creek) to the bathroom to remove the charcoal you have just rubbed into your very own precious face.

Like everything at 2 a.m., it started innocently enough: you were drawing your face on paper in charcoal and switched to drawing charcoal on your face.

The world. Is magnified. At this hour.

xvi.

Thoughts are more vital at 2 a.m. I wonder if there are statistics on the hour. Do more people die? Do they create masterpieces? Do they change their lives, lose their minds?

What I find: at 2 a.m. most bars close worldwide; daylight saving begins and ends at 2 a.m., and by 2 a.m., you are most likely to give birth outside of the hospital without intervention—which shows just how regulated our lives have become. In the hospital, you are more likely to have your baby during so-called “normal” hours: between 8 a.m. and noon.

Medieval monks were required to go to bed around 7 p.m. and then wake up for matins around two in the morning. Matins: morning prayer said or chanted; also, matin: the morning song of birds. This last is the one I relate to the most. The sound of insomnia—the sound of 2 a.m.—is best described as the silence of making eye contact with a bird in the middle of the night.

Ekirch says our “deeper first sleep [lasted] from sunset until around 2 a.m.,” followed by about an hour of wakefulness before second sleep. During this wakeful time, we might read, have sex, visit with neighbors, pray, or simply contemplate our dreams. Now, we call this insomnia.

Statistics say you are more likely to die at 11 a.m. (by natural causes); artists are most productive starting around 4 a.m.; and people are more likely to make life-changing decisions before their thirtieth birthday—no mention of the hour. If you believe the internet, “nothing good happens after 2 a.m.,” and people report browsing Facebook for pictures of exes and aimlessly scrolling Netflix for something to watch after the hour. I am guilty of the latter but not the first.

I’ve lain here too long again. I’ve forgotten everything again. And on television, everyone was sad. Everything was rotten.

xvii.

I take my sons to the Lost Egypt exhibit at the science museum and we spend hours absorbing the hieroglyphs. The mummies. The sarcophagi. The archeology and tomb art. I can just barely resist running my hands along the indentations in the cold stone blocks, resting my body alongside the wrapped bodies. The children are intrigued that all the things I have been drawing and researching for months are in a museum. I gain slow ground on motherhood and sleep.

Perhaps insomnia is not a state to fight. What if it is simply my way of experiencing the hours of the night? I am doing all right, after all. I feel rested. I no longer go crazy in the bathroom, terrified of 4 a.m. When I read on WebMD all the strategies for combatting insomnia, I come away feeling much the same as I did after reading advice on migraines: I want to tell them they know nothing of 2 a.m.; know nothing of dark rooms and silence; of me. I develop a strange affinity for Roger Ekirch, the Egyptians, and my insomnia.

O insomnia. Midnight lover. My drunken friend.

notes.

• All writing and research done during bouts of insomnia, between 2 and 4 a.m. Revisions and erasures completed after.

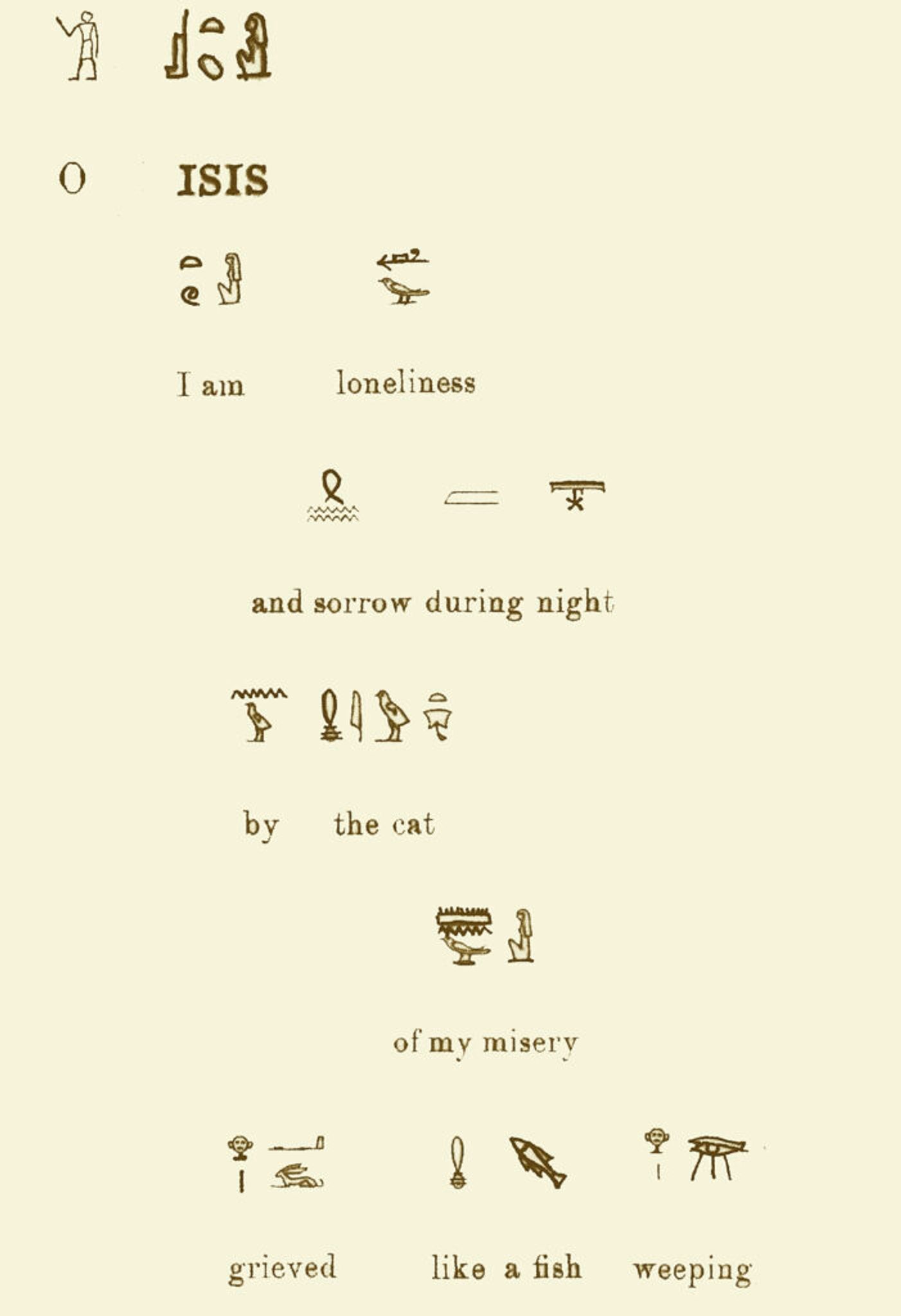

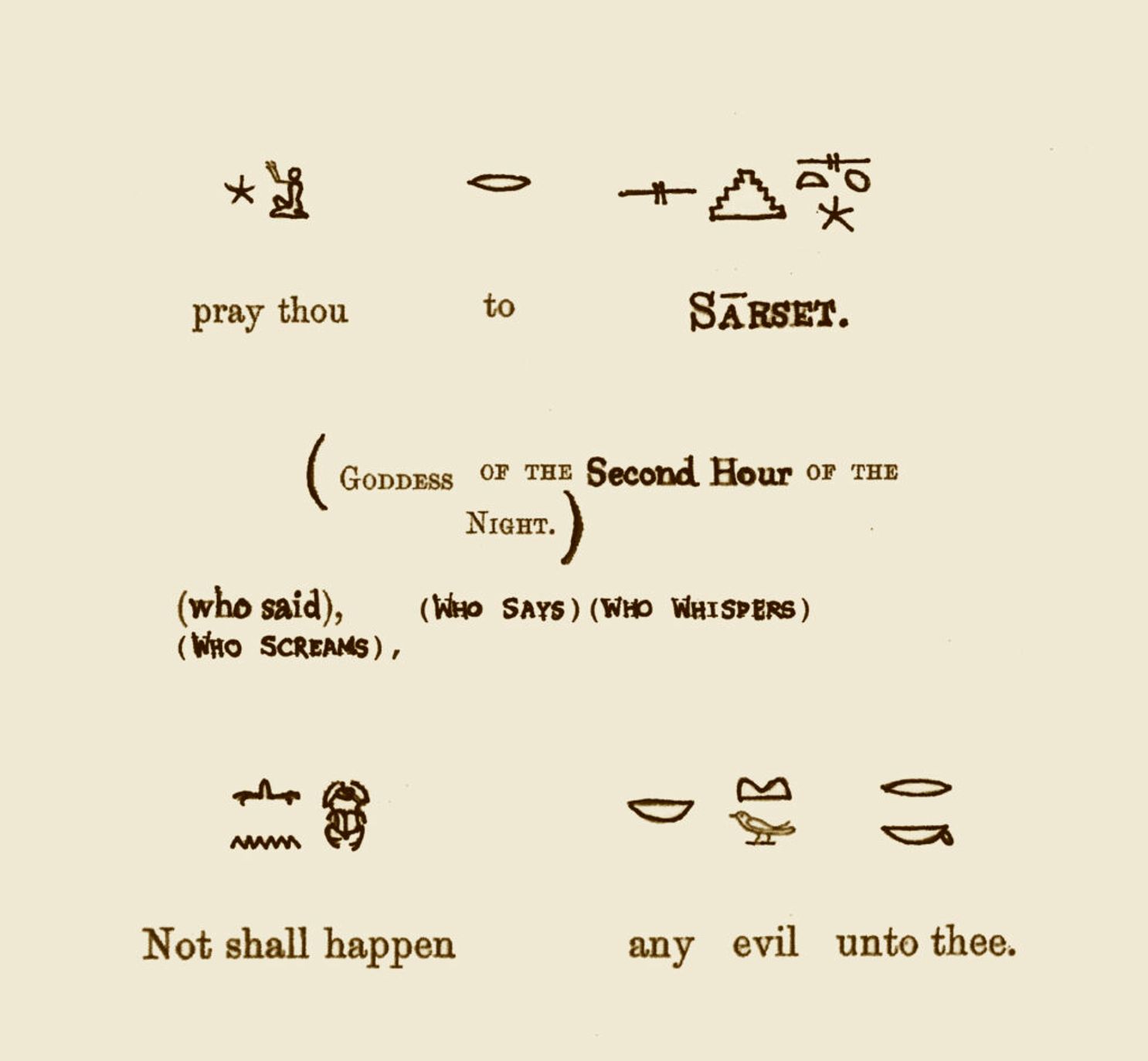

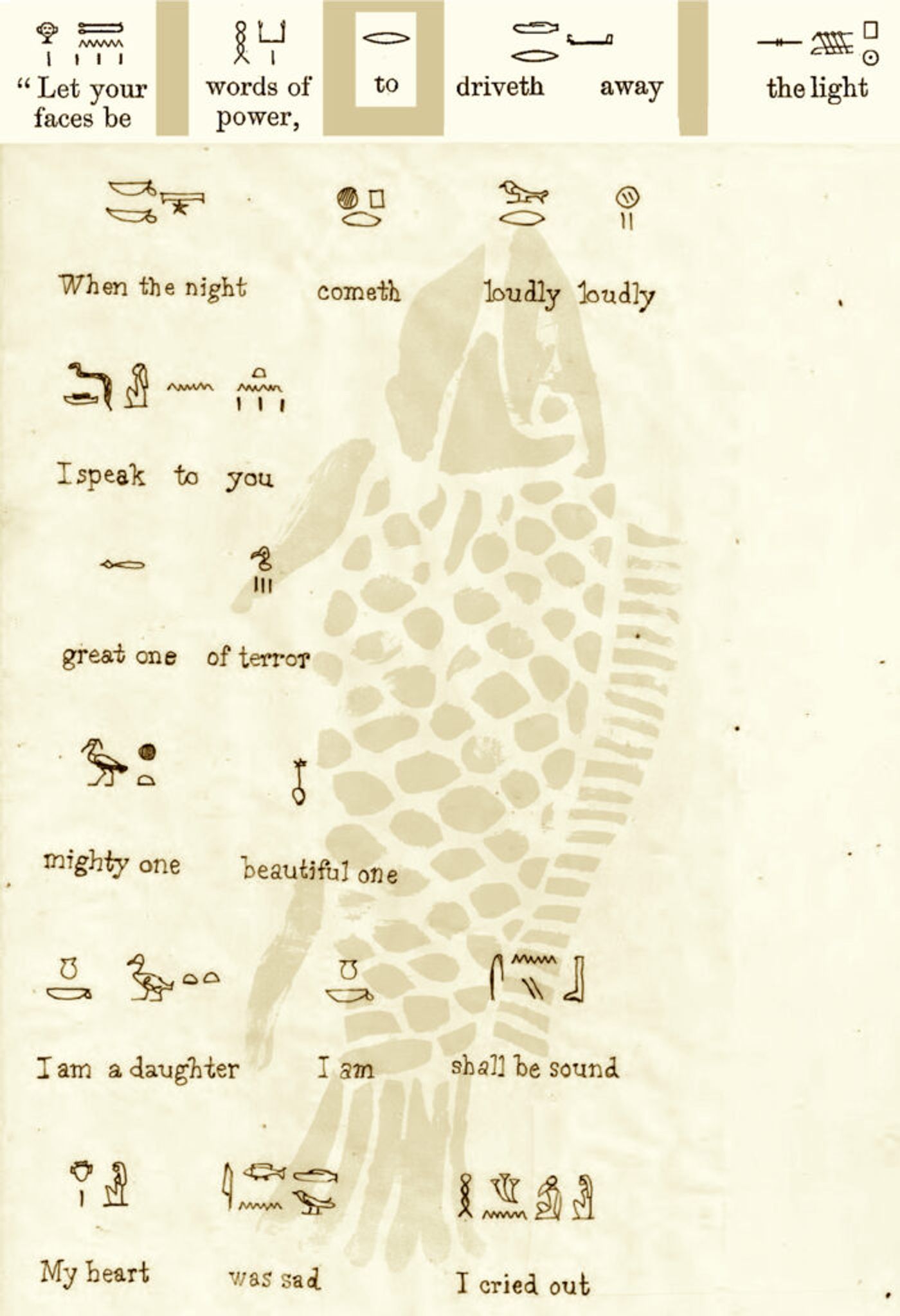

• During this time, I read all 540 pages of volume one of the book, The Gods of The Egyptians: Studies in Egyptian Mythology (1904) by E. A. Wallis Budge, from which all the erasures are created. Pray thou to Sarset is from “Miscellaneous Gods: The Gods and Goddesses of the Twelve Hours of the Night” (300) and “The Sorrows of Isis” (231). Sorrow & Loneliness is compiled from “The Sorrows of Isis” (222-240). Let your faces be words of power to driveth away the light is compiled and translated from “Hymn to Osiris” (162-175). Hand-drawn on graphite fish print.

• ISIS was the female counterpart of OSIRIS in the dynastic period. We may assume she was also associated with the god in this capacity, and as he was originally a water spirit or a river god, she must have possessed the same characteristics.

• First historical treatment: as a hypnotic, ancients described poppy seed for insomnia relief in the Egyptian medical papyri.

• Lavender, used to preserve mummies, is an herbal sleep remedy. Belief about death as eternal sleep.

• To soothe my middle son, to ready him for rest, I bathed him in lavender water, lathered him in lavender lotion, tried anything lavender to end the deprivation of sleep.

• Chamomile. Sacred plant. Offer to the gods. Induce quiet, serenity before sleep.

• The fascination for everything Egyptian is referred to as Egyptomania.

• The hieroglyph for sleep is a bed.

• An open eye is the representation for dream. Literally: to come awake.

• Dream is ‘bed’ + ‘open eye’ = awaken within sleep. [Lucid dream.]

• There is no expression for rest. Note similarity of dream to underworld. You do not rest. You either dream or you die.

• Ancient Egyptians believed the soul (ba, represented by a human-headed bird floating above the sleeping body) would travel beyond the physical body during sleep. Sleep was viewed as similar to death / the person is in a different state / world.

• I am not a spiritual person. I do not believe in any of this. But the night plays tricks on your psyche. The night. The never-ending night. I recall there was a time I slept.

• Also worth noting is the article, “Crossing Over: How Science Is Redefining Life and Death” (National Geographic, April 2016). Careful, this is deeply disturbing, with its research-based discussion of near-death experiences and the gray zone, not to mention thukdam—a perfectly freaky phenomenon “in which a monk dies… with no physical decomposition for a week or more.” After reading this, you will suddenly be considering ideas once taken for granted, such as: dead is dead.

• Sleep = doorway to mysterious world of afterlife. Communication with dead and his gods. Some sleep rituals mirror preparation for death.

• Coffin Texts: to help the dead navigate the afterlife, spells and incantations were inscribed into their coffins. While these “maps to the afterlife” were previously only accessible to the king and his family as the Pyramid Texts, the Coffin Texts meant anyone who could afford to have them copied could also have access to the afterlife. I have, inadvertently, come to use these as a type of bedtime prayer, to rescue me from my sleep paralysis, nightmares, and insomnia.

• Coffin Text 74: “Oh sleeper, turn about in this place which you do not know, but I know it. Come that we may raise his head. Come that we may reassemble his bones.”

• Coffin Text 69: “Oh lift up your head, says Re. Detest sleep, hate inertness, be far from them as Horus, that you may live.”